Sedentary Behaviour in Disability: Why High Sitting Time Leads to Further Health Complications

What is Sedentary Behaviour

Have you ever experienced a persistent sense of tiredness that significantly reduces your motivation to engage in daily activities? This sensation is frequently experienced by individuals following a long and demanding day at work, as well as during weekends when people often seek opportunities to rest and recover from the pressures of the week. As a result, many individuals choose to minimise physical movement and instead participate in activities that require little to no physical effort. This pattern of prolonged physical inactivity is commonly referred to as sedentary behaviour and has become increasingly prevalent in modern society due to changes in lifestyle and work environments.

Sedentary behaviour is formally defined as any waking activity characterised by low energy expenditure and minimal bodily movement, during which individuals remain seated or reclined for extended periods of time. In contemporary daily life, sedentary behaviours are widely observed across various settings, including at home, in educational institutions, and within workplaces. Common examples include sitting or lying down while using mobile devices such as smartphones or tablets, engaging in prolonged periods of binge-watching television programmes or online streaming content, and spending several consecutive hours working at a desk in front of a computer. The widespread adoption of technology and screen-based activities has further contributed to the rise of sedentary behaviour, making it a routine aspect of daily living for many individuals.

Sedentary behaviour found in those with disability:

Numerous studies have demonstrated that the average individual fails to meet the recommended weekly levels of physical activity, a trend that may contribute to the development of various adverse health outcomes and long-term health complications. Insufficient engagement in physical activity has been closely associated with increased risks of chronic conditions, including obesity, cardiovascular disease, and reduced overall physical fitness. When examining populations with disabilities, levels of sedentary behaviour are even more pronounced. Research indicates that sedentary behaviour among children with disabilities aged between 6 and 11 years is approximately 66% higher when compared to their typically developing peers (Gehricke, et al 2020).

This substantial increase in sedentary behaviour among individuals with disabilities can be attributed to a range of factors that are directly associated with the nature and severity of their conditions. One significant contributing factor is the presence of limited motor skills, which can restrict an individual’s ability to participate in physical activity effectively and safely. Limitations in motor skills may affect fundamental movement abilities such as walking, throwing, catching, kicking, jumping, and maintaining balance. These impairments can create additional barriers to active participation in physical or recreational activities, thereby increasing reliance on sedentary behaviours and reducing overall levels of physical movement.

Further health complications + Physical Activity Guidelines for those with sedentary behaviours

Individuals who engage in higher levels of sedentary behaviour are at an increased risk of developing future health complications. Prolonged sedentary time has been associated with cardiovascular conditions such as heart disease and hypertension, metabolic disorders including obesity and type 2 diabetes, and mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, and reduced emotional wellbeing. These risks are further exacerbated when sedentary behaviour is combined with poor dietary habits and unhealthy lifestyle choices.

To mitigate these risks, individuals are strongly encouraged to reduce sedentary behaviour by engaging in regular physical activity. Australian physical activity guidelines recommend participation in both aerobic and resistance-based exercise. Aerobic activities may include walking, running, boxing, swimming, and cycling, while resistance training can involve free weights, fixed machines, resistance bands, and plyometric exercises. Exercise duration varies depending on intensity and modality. For example, individuals engaging in moderate-intensity aerobic exercise are advised to complete 150–300 minutes per week, whereas those participating in vigorous-intensity aerobic exercise should aim for 75–150 minutes per week. In addition, resistance training is recommended at least twice per week, with a focus on full-body sessions (AIHW, 2025).

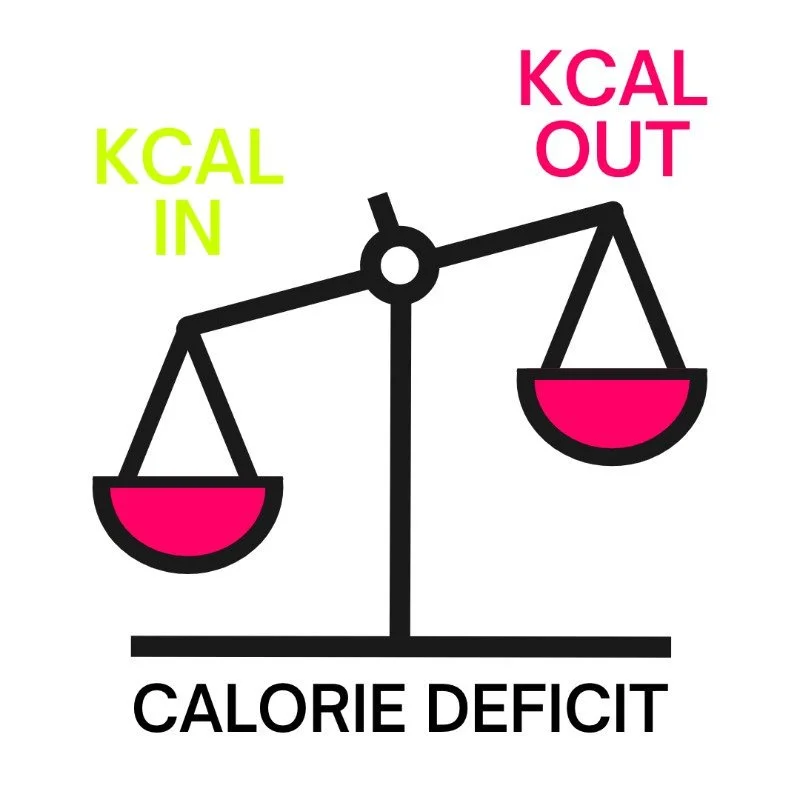

During digestion, dietary carbohydrates are broken down into glucose, which is used as a primary energy source. Excess glucose that is not immediately utilised is stored in the bloodstream and liver, contributing to weight gain and increasing the risk of associated comorbidities. However, aerobic exercise promotes the utilisation of stored glucose and carbohydrates for energy, resulting in a caloric deficit that supports weight reduction and improved blood glucose regulation (Jayedi, 2024). Furthermore, research by Yu (2022) indicates that increasing physical activity and reducing sedentary behaviour significantly improves mental health outcomes, lowering the risk of anxiety and depression. Evidence suggests that combining aerobic and resistance training within a single exercise session produces the greatest benefits for mental health, particularly in the management of depression and schizophrenia.

Articles

Lynch, L., McCarron, M., McCallion, P., & Burke, E. (2021). Sedentary behaviour levels in adults with an intellectual disability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HRB Open Research, 4, 69. https://doi.org/10.12688/hrbopenres.13326.3

Marquez, D. X., Aguiñaga, S., Vásquez, P. M., Conroy, D. E., Erickson, K. I., Hillman, C., Stillman, C. M., Ballard, R. M., Sheppard, B. B., Petruzzello, S. J., King, A. C., & Powell, K. E. (2020). A systematic review of physical activity and quality of life and well-being. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 10(5), 1098–1109. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibz198

Gehricke, J.-G., Chan, J., Farmer, J. G., Fenning, R. M., Steinberg-Epstein, R., Misra, M., Parker, R. A., & Neumeyer, A. M. (2020). Physical activity rates in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder compared to the general population. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 70, Article 101490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2019.101490

Sowa, M., & Meulenbroek, R. (2012). Effects of physical exercise on Autism Spectrum Disorders: A meta-analysis. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(1), 46–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2011.09.001

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare), 2025. Physical Activity - Australian Guidelines https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/physical-activity/physical-activity

Jayedi, A., Soltani, S., Emadi, A., Zargar, M.-S., & Najafi, A. (2024). Aerobic Exercise and Weight Loss in Adults: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. JAMA Network Open, 7(12), e2452185. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.52185

Yu, Q., Wong, K.-K., Lei, O.-K., Nie, J., Shi, Q., Zou, L., & Kong, Z. (2022). Comparative Effectiveness of Multiple Exercise Interventions in the Treatment of Mental Health Disorders: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Sports Medicine - Open, 8(1), Article 135. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-022-00529-5